CONSERVATION

We were bequeathed astonishing beauty and wilderness; what we do with it reflects who we are, and what we value.

Philosophy

Everyone who enjoys the outdoors has an implicit contract with Nature. We head out into her mountains and waters for many reasons: recreation, scenic inspiration, challenge, and personal renewal. It is up to us to keep her healthy.

Modern technology allows astonishing power over Nature. It provides us with opportunity to live comfortably almost anywhere, and also gives us tools that allow us to rip away mountaintops, dig 3000 foot deep holes like the Berkeley Pit, dam the world’s largest rivers and flood canyons and valleys.

When we have such power to change things, it is important to think carefully about what we want to change, and why.

It wasn’t always like this. The late 1800s was a hard time where we had to carve our world out of Nature, pouring energy into the basics of life, and little concern about conservation.

Most of the environmental destruction of my beautiful home state of Montana came as we moved out of that era. Men began to wield more power, the forests, minerals, and rivers were put into service for a fast growing nation.

The wilderness seemed endless back then, and technology for controlling pollution didn’t exist. Montana’s rivers provided electricity, her forests gave timber. The mines provided jobs and brought up metals that were used in a tidal wave of new inventions: to light cities, make telephones and telegraphs, forge high quality steel for railroads and high rise buildings. Travel changed from horses to steam engines. Most of the technology that makes our lives better had its roots in the inventions and hard work of that era.

The power was wielded like a giant scythe deep into our landscape. Looking at the problems that are left, it’s time to consider carefully our contract with Nature. We have the benefit of two hundred years of experience; it’s clear our love of Nature has to be balanced with the need for the raw materials that make our modern lives possible.

Nature is endlessly creative and can heal herself, but she moves on a longer time scale than men’s lifetimes. If we want to see changes ourselves and maintain a beautiful world, we need to use our power more deftly and with greater thought, so we minimize harm we create and help Nature heal the places where scars remain.

It is worth the effort. Stand back and admire the history of our state and the sweep of Nature around you. A billion years of geology is spread out in the mountains you see. Remember, Montana’s continental divide is the source of rivers that run to three oceans, spreading the snow melt of our peaks to far shores. We are called the Big Sky for good reason – the breadth of our land matches the great horizons.

The goal of each era changes and here in the 21st Century, all of us who enjoy this spectacular place must balance the conservation of our land with our need to provide for the present and future.

We were bequeathed astonishing beauty and wilderness, and a rich environment. We know more now. Let’s be careful.

The Clark Fork River Reborn

Autumn 2011

Last winter Nature treated us to record snowpack and a spring runoff that reached flood stage for nearly two months. At the Clark’s Fork River in Missoula, hundreds of people gathered on the bridges in town to stare wide-eyed at the water rushing by, carrying full sized trees and debris. There was worry that there might be major landslides upstream because this was the first runoff since the Milltown dam had been removed.

Built in 1906 at the confluence of the Blackfoot and Clarks Fork rivers, that dam’s original purpose was to store water in the Milltown reservoir and generate power. Ironically, the flood of 1908 filled the basin behind it with sediment that never allowed the dam to do much of either.

It stood athwart the river seven miles upstream from Missoula for over 100 years accumulating sediments toxic with arsenic, cadmium, lead, copper and zinc, all washed down from mining and smelting that had been going on since the mid-1800s in Butte and Anaconda. Poisoned from practically the headwaters down by the traditional extraction industries that ruled the west, the toxins killed thousands of fish and gradually seeped into the aquifer and started showing up in Missoula’s wells downstream.

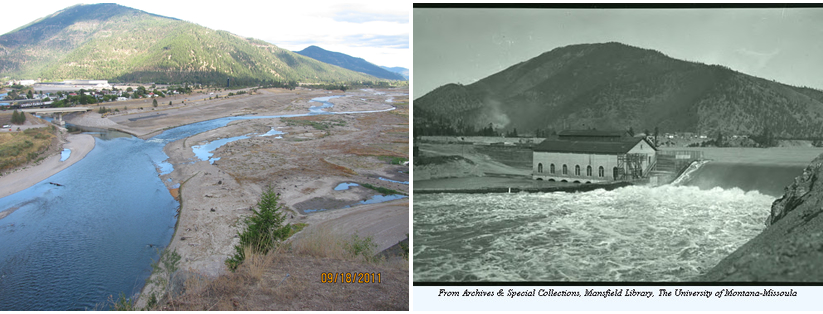

Restoration projects have been under way on this 110 mile stretch of river, which forms the largest superfund site in the US. The headwaters were rerouted into holding ponds and bird habitat. Over 6 million cubic yards of tainted mud were removed from the Milltown reservoir’s bottom. The Milltown dam and a 120 year old dam just upstream on the Blackfoot river at a timber mill were removed in the summer of 2011 and the rivers joined again. With the spring flood of 2011, Nature had her way with both rivers for the first time in over a century.

As the water dropped and cleared up through the summer and into the fall, changes to the river became more and more obvious. Recently I snuck through the former reservoir section at the confluence that is still off limits to river travel.

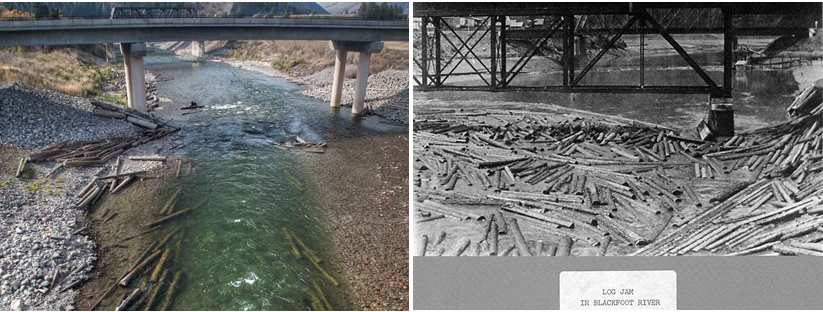

With the removal of the dams, both rivers sped up and cut down 20 to 30 feet into cobble and sediment layers that had not seen substantial current for a century. The cutting of the riverbed on the lower Blackfoot was perhaps the most dramatic. Over about the distance of mile, it completely changed multiple bends, rearranged the river bottom, dropped the water level, undercut banks, and laid bare old bedrock ledges and huge boulders long covered. It unearthed thousands of logs buried from the huge log drives at the turn of the century, where all cut timber was pushed into the river and spring floods transported them downstream to the Bonner mill in gigantic matchsticked log jams filling the river for miles. Buried for all this time, thousands of them reappeared and were pushed up to 60 miles downstream, through and below Missoula along different parts of the banks and underwater.

The stretch of the Clark Fork from above the dam site down into Missoula was transformed as well. Huge new expanses of cobble bars appeared right where the Milltown dam powerhouse, spillway, and concrete rip-rap used to be. Sections of riverbed that had only scoured larger cobbles, thick muddy sediments, or algae-plumes in late summer, were replaced by acres of fine sand and perfectly sorted, multi-colored gravel beds. The river looks like a clean mountain stream instead of the largest EPA superfund site in the US. Paddling along in disbelief, I saw Great Blue Herons, osprey, deer, and a bear drinking in the river, and around one corner, two baby bald eagles shrieking in joy as they learned to fly in the blustery afternoon winds. Before our eyes, the river is reborn.

Printed in Canoe and Kayak Magazine (2011)

River Conservation Benefit:

February, 2011 Hood River Oregon Premier of Wildwater, also showing The Greatest Migration, Seasons: Spring with Kate Wagner, Run Rogue Run, and

Photo permissions:

South Fork Payette River photo: Mike Leeds